Rent or food. Gas or car payment. Healthcare or bankruptcy.

These are the choices that Americans face in 2022. But why? You’re not in this position because you didn’t pull yourself up by your bootstraps hard enough; you bust your ass every week. No, you’re in this hell because a group of privileged monkeys in suits decided it, and the worst part is, is that you put them there to supposedly serve your interests.

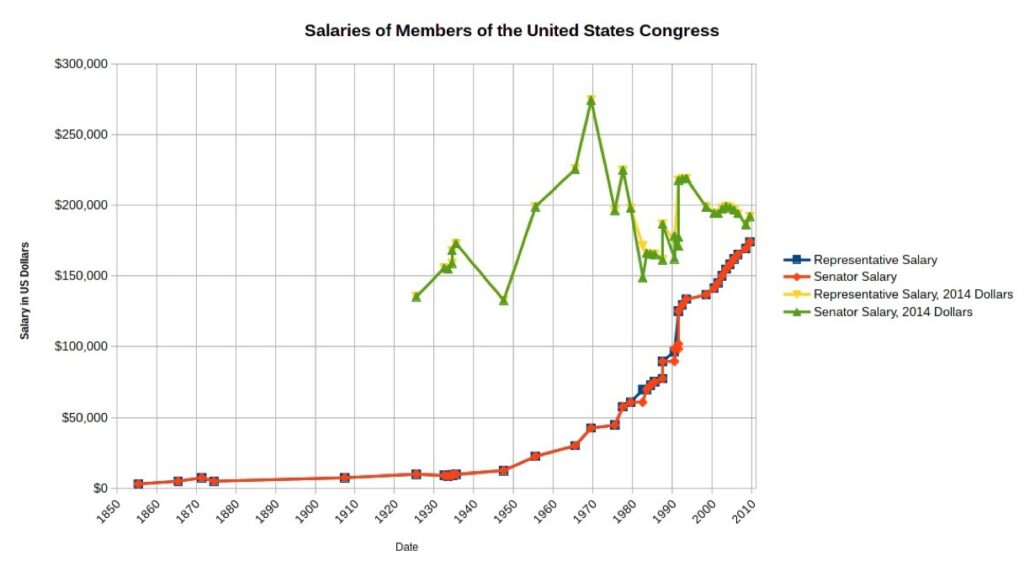

Over the last 150 years, serving members of the United States Congress have not only enjoyed healthy salaries far above poverty levels, they’ve also approved a steady stream of increases in compensation for themselves.

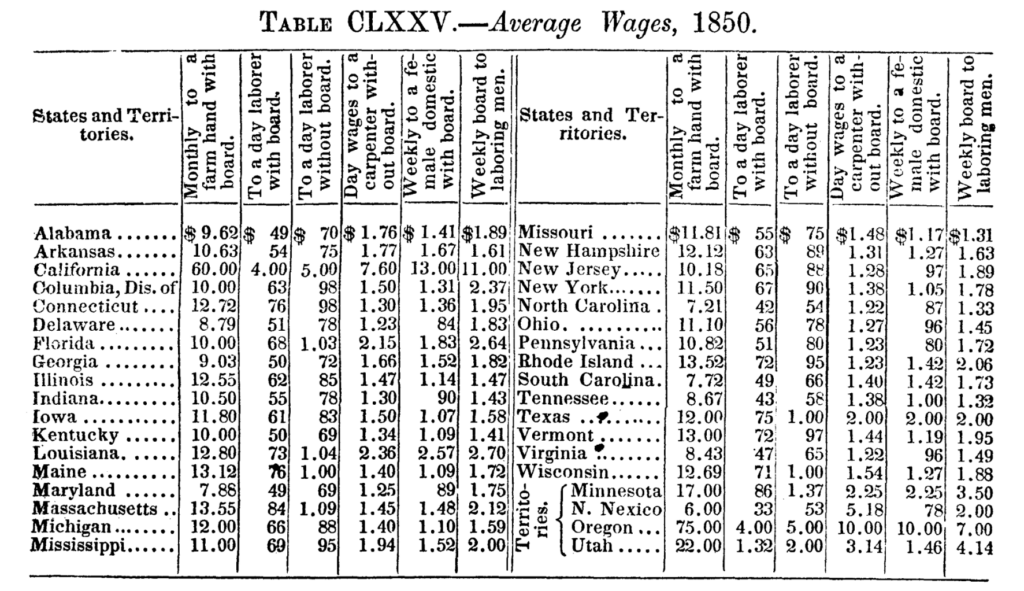

In 1855, members of the United States Congress earned $3,000/yr—a comfortable $100,791.72 in today’s dollars. The average monthly wage of a farmhand at this time was $75/month at best ($30,237.52/yr in 2022 dollars), and $7.21/month at worst ($2,906.83/yr in 2022 dollars).

Runaway Raises

Despite already netting over 300 percent of what a well-compensated laborer would earn, the fine members of the United States Congress would not be denied. In 1865, at the behest of a devaluing dollar, the salary of an active member of the United States Congress was increased to $5,000/yr ($89,661.35/yr in 2022 dollars), and then once more in 1871 to $7,500/yr ($179,690.16/yr in 2022 dollars).

Between 1871 and 1874, members of the United States Congress were compensated handsomely, earning 60% in 2022 dollars in only three years ($539,070) what they had earned in the previous ten years combined ($896,610).

From 1874 through 1906, members of the United States Congress would receive $5,000/yr. However, despite appearing to be a fixed pay decrease at face value, once adjusted for inflation across multiple years, it instead nets a hefty wealth increase. In 1874, $5,000 had the same buying power as $128,200.00 in 2022 dollars, and by 1884, that same $5,000 was equivalent to the buying power of $149,130.61. A decade later, in 1894, $5,000 had the net buying power of $169,939.53 in 2022 dollars.

But then suddenly, after 30 years of continuous wealth growth, and a peak buying power in 1900 of $173,985.71 (in 2022 dollars) for that same $5,000 salary, the dollar devalued the year after, and continued to do so. By 1907, that value had dropped to $155,476.60 (in 2022 dollars).

In response to this diminishing buying power, the members of the United States Congress promptly approved a salary increase that same year, returning themselves to $7,500/yr—which by the way—is $233,214.89 in 2022 dollars.

And yet, it wouldn’t be long before the United States Congress would find themselves in an all-too-familiar situation, and by 1917, that $7,500/yr salary would continue to devalue, eventually netting only $171,267.19 worth of buying power in 2022 dollars, and subsequently, by 1922, a mere $130,489.29.

Seemingly dissatisfied with their wealth loss, and ignoring every alarm regarding the 50 percent devaluation of the dollar over the last 15 years, yet another salary adjustment was passed in 1925, this one marking the first time that a serving member of the United States Congress’ salary breached $10,000/yr ($167,026.29 in 2022 dollars).

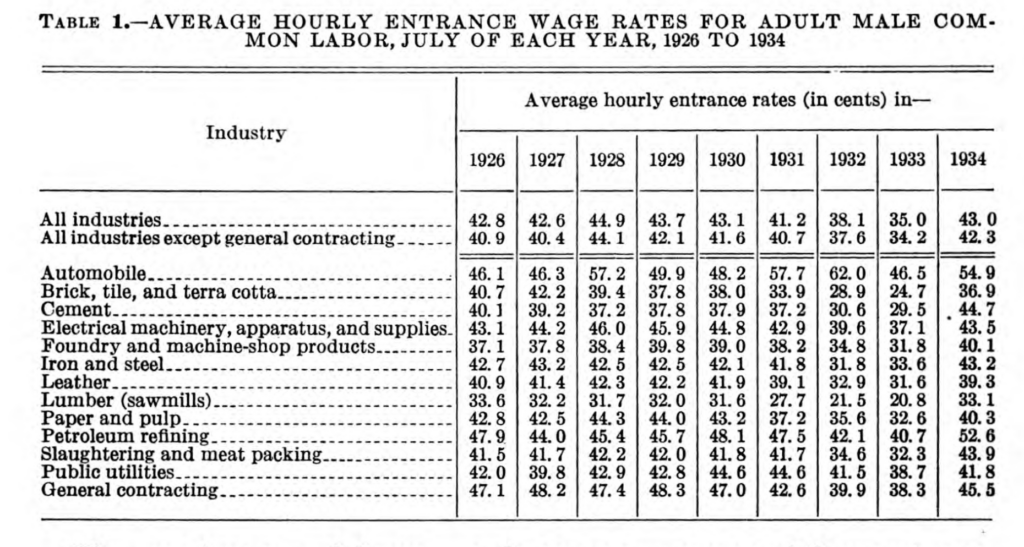

Let’s check back into what a common laborer would make in 1925:

Yikes.

In 1855, a common farmhand earned at best $75/month, which after some basic arithmetic, comes out to $900/yr in 1855 dollars (which, if you recall from earlier, is $30,237.52 in 2022 dollars). By 1925, a common laborer earned—on average—roughly $894.44/yr (or the equivalent of $14,948.85/yr in 2022 dollars).

Over the course of seven decades, and on the verge of the greatest economic collapse the United States had ever seen, common laborer wages peaked at $900/yr—devalued dollar be damned—while the members of the United States Congress thrived.

The Pattern Emerges

This pattern of self-approved salary increases continued for decades: as the dollar devalued, and its equivalent buying power diminished, the members of the United States Congress increased their own salaries to compensate for the difference.

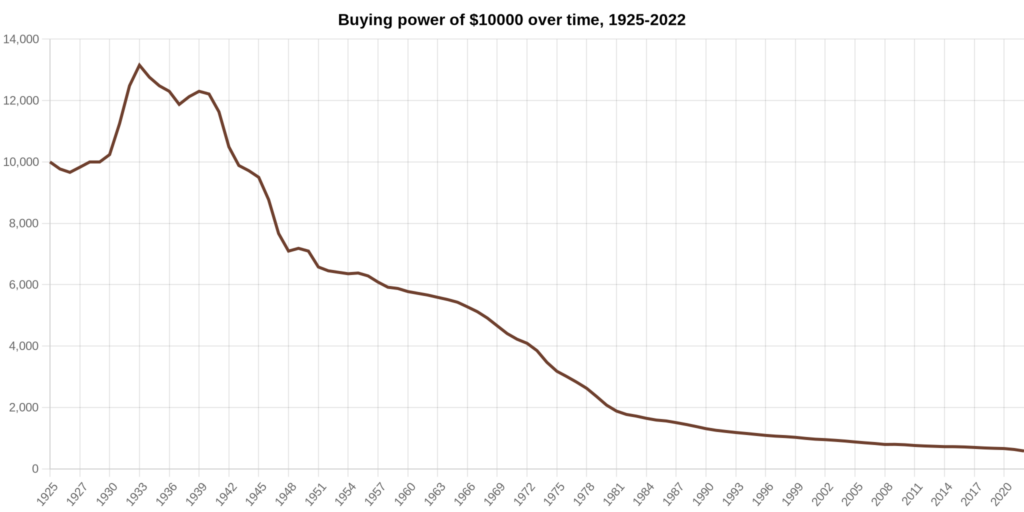

Now, let’s compare that to the buying power of the 1925 salary of $10,000 for a sitting member of the United States Congress, over time:

Striking. As the buying power of the dollar diminished, the members of United States Congress increased their salaries with eerie precision. However, this is not the result of luck, or pure chance. No, instead, this shows that the United States Congress has thoroughly understood the impact of inflation on wages for decades, and has continuously moved to protect their own interests without delay or hesitation.

Of course, it makes a huge difference to adjust for inflation if you’re already starting at a fair, living wage. After all, adjusting peanuts for inflation will only give you peanuts in return, which leads us to the true issue at hand.

The Rub

In 1939, the United States Congress formally took control of wages in the United States by passing the Fair Labor Standards Act, which established a little thing known as the federal minimum wage. This was made possible by the powers granted to the United States Congress by the Constitution, specifically Article 1, Section 8, Clause 3, more commonly known as the Commerce Clause.

At least in theory, this would seem like an arguably good thing: a third-party, authoritative institution with no direct interest in employer’s profits would enforce a fair wage, outlaw child labor, and ensure proper compensation for overtime.

Except, the FLSA did not establish any sort of guidance for how a fair wage should be calculated, let alone defined, which has presented a problem for the Department of Labor—a problem the United States Congress is seemingly very aware of—and one they did not hesitate to solve, at least for themselves.

And while I have no proof of this, I would wager that every person would agree that a fair wage should be defined as the ability to secure basic human rights, such as housing, clothing, food, water, and so forth.

Yet, despite runaway inflation that is driving prices for everything into the stratosphere, and a constant erosion of every dollar’s value in your wallet (or purse), the United States Congress has steadfastly refused to amend the FLSA, and define a fair, living wage for all Americans, once and for all.

If we don’t demand better for ourselves, nobody will.